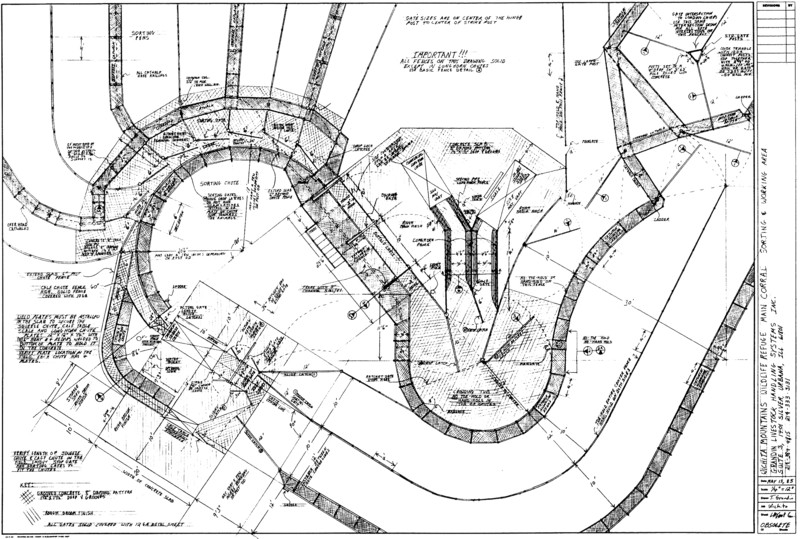

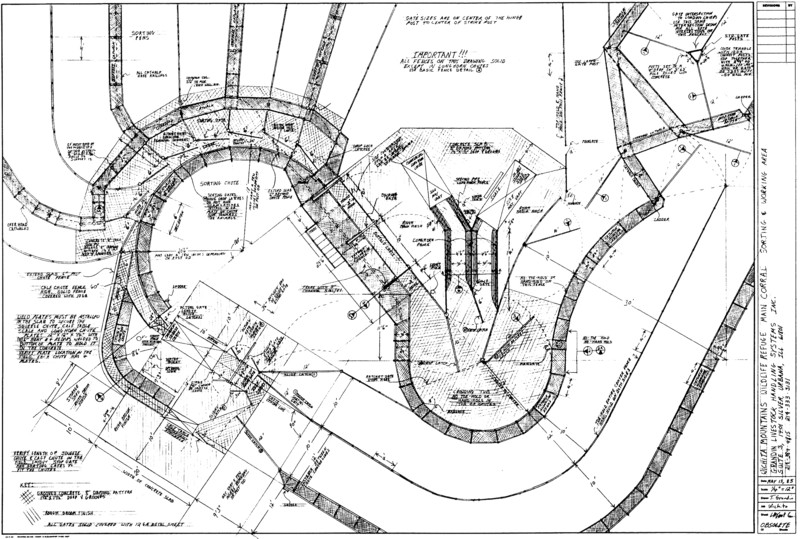

Figure 1: Drawings of livestock handling facilities by Temple Grandin dated May 13, 1985.

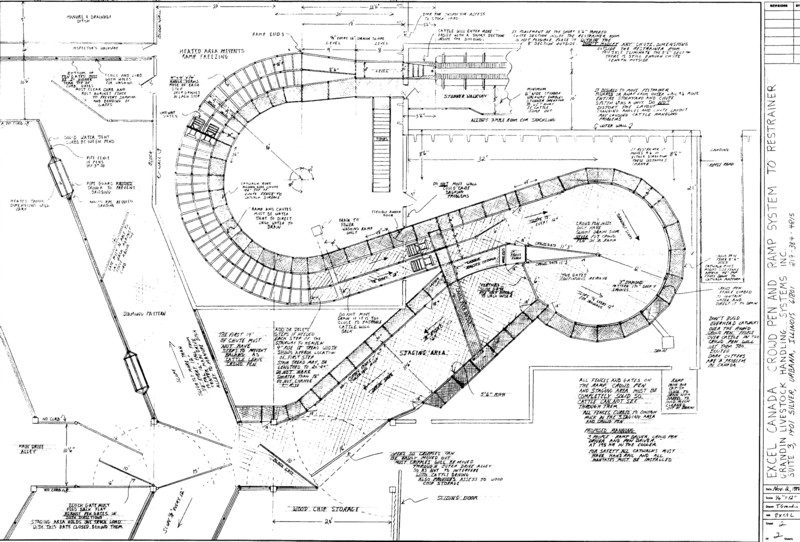

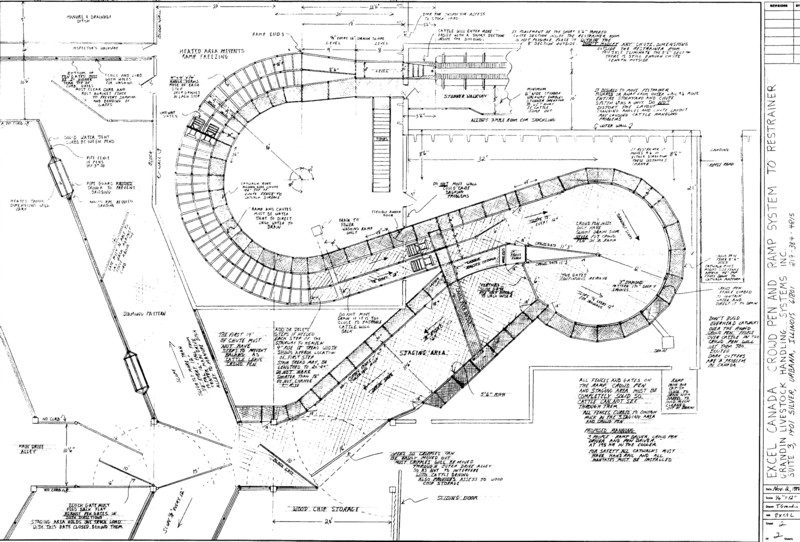

Figure 2: Drawings of livestock handling facilities by Temple Grandin dated November 2, 1987.

Department of Animal Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society(2009) 364, 1437-1442

doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0297

My mind is similar to an Internet search engine that searches for photographs. I use language to narrate the photo-realistic pictures that pop up in my imagination. When I design equipment for the cattle industry, I can test run it in my imagination similar to a virtual reality computer program. All my thinking is associative and not linear. To form concepts, I sort pictures into categories similar to computer files. To form the concept of orange, I see many different orange objects, such as oranges, pumpkins, orange juice and marmalade. I have observed that there are three different specialized autistic/Asperger cognitive types. They are: (i) visual thinkers such as I who are often poor at algebra, (ii) pattern thinkers such as Daniel Tammet who excel in math and music but may have problems with reading or writing composition, and (iii) verbal specialists who are good at talking and writing but they lack visual skills.

My mind is associative and does not think in a linear manner. If you say the word 'butterfly', the first picture I see is butterflies in my childhood backyard. The next image is metal decorative butterflies that people decorate the outside of their houses with and the third image is some butterflies I painted on a piece of plywood when I was in graduate school. Then my mind gets off the subject and I see a butterfly cut of chicken that was served at a fancy restaurant approximately 3 days ago. The memories that come up first tend to be either early childhood or something that happened within the last week. A teacher working with a child with autism may not understand the connection when the child suddenly switches from talking about butterflies to talking about chicken. If the teacher thinks about it visually, a butterfly cut of chicken looks like a butterfly.

During the last 5 years, I successfully used this method to fix some of my health problems. Most people have to have a theory first, and then they try to make the data conform to it. My mind works the opposite way, I put lots of little pieces of data together to form a new theory. I read lots of journal papers and I take little pieces of information and put them together as if completing a jigsaw puzzle. Imagine if you had a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle in a paper bag and you had no idea what the picture on the box is. When you start to put the puzzle together, you will be able to see what the picture is when it is approximately one-third or one-quarter of the way completed, When I solve the problem, it is not top-down and theory driven. Instead, I look at how all the little pieces fit together to form a bigger picture.

When I was in college, I called this finding the basic principle. On everything in life, I was overwhelmed with a mass of details and I realized that I had to group them together and try to figure out unifying principles for masses of data.

Researchers have found that people with autism often have difficulty in forming new categories (Minshew et al. 2002). When I was a child, we played lots of games such as Twenty Questions that forced me to get good at thinking in categories. Category formation is a fundamental property of the nervous system. Brains are wired to put visual information into categories (Freedman et al. 200 1). The hippocampus also has the ability to determine whether or not similar photos of objects are the same or different (Bakker et al. 2008). Observations of stroke patients have shown that brain damage can cause them to lose their ability to categorize objects such as tools, but they can still categorize vegetables and animals (e.g. Mummery et al. 1998).

In my case even abstract questions are answered by putting photo-realistic pictures into categories. One time I was asked 'Is capitalism a good system?' To answer this question, I put pictures from countries that had different types of governmental systems into the following categories: (i) capitalistic, (ii) capitalistic/ socialistic, (iii) socialistic, (iv) benevolent dictatorship, (v) brutal dictatorship, and (vi) war and chaos. These pictures were taken from my memory and they are from experiences travelling or the news media. My answer was that I absolutely do not want to live in a brutal dictatorship, or war and chaos. Pictures helped me make a choice because in the last two choices I see news photos and TV images of killing and destruction.

My ability to provide a well thought-out answer has greatly improved with age because I have travelled more, and have more pictures both from actual experiences and from reading. They can be sorted into the different categories. When I read, I convert text to images as if watching a movie. The images are then stored in my memory. In college, I photocopied images of my class notes into my brain. When I was a teenager, answering the question about capitalism in an intelligent manner would have been impossible. I simply did not have enough experiences or enough information in my memory to answer it.

As an undergraduate, I did an honor's thesis on the subject of sensory interaction. Here the question was how a stimulus to one sense, such as hearing, affects the sensitivity of other senses. I had over 100 journal papers and I numbered each paper. On small pieces of paper, I typed the major findings of each study. I then pinned hundreds of little slips of paper on a bulletin board. I called it my logic board. Since my thinking is totally non-sequential, I had to develop a way so I could see a display of all the information at the same time on the bulletin board. To discover the categories and concepts, I started pinning the slips of paper into different categories. It was very time-consuming. As I gained more experience with sifting through scientific research, I no longer needed the bulletin board. I became better and better at finding unexpected clues, such as many deafness treatment papers being in arthritis journals. From my previous scientific knowledge, I made the association of rheumatoid arthritis to autoimmune, and therefore saw that ear damage would work the same way as joint damage.

When I was young, my thinking process was extremely slow because I was less skilled at finding the basic principle from the masses of data. But skills in people on the autism spectrum still develop when they are adults. The more research I did analyzing the results of scientific studies, the better I got at it. I always read the methods section of a paper carefully so I can visualize how the experiment was done. Differences in methods often explain conflicting results of scientific studies.

Figure 1: Drawings of livestock handling facilities by Temple Grandin dated May 13, 1985.

Figure 2: Drawings of livestock handling facilities by Temple Grandin dated November 2, 1987.

There is a wide range of brains that should be considered part of normal variation. A brain can be built with larger fast circuits that facilitate social communication or smaller, slower circuits that improve cognition in a specialized area.

In any information processing system, there are always trade-offs. Brains with high-speed connections to many distant areas will be fast and details will be missed. Research shows that normal brains fail to process details that the autistic person perceives (see Happe & Frith 2009; Happe & Vital 2009). My model for visualizing the different types of brains is a large corporate office building. The president (frontal cortex) is located at the top and he has telephone and computer connections (white matter) to offices throughout the building. I hypothesize that in a highly social brain, the frontal cortex has high-speed connections that go mainly to the department heads in the building. The network is fast and details are omitted. In the autistic/Asperger brain, the frontal cortex is poorly connected, but the visual and auditory parts of the brain (technical nerd departments) have lots of extra local connections providing better processing of detailed information.

In 2006, Nancy Minshew and her colleagues performed a method called diffusion tensor imaging on me. They found a huge white fiber tract that runs from deep in my visual cortex up to my frontal cortex. It is located in the brain slice made at the level of my eyes. It is almost twice as large as my sex- and age-matched controls. I used to joke about having a big high-speed Internet line deep in my visual cortex. It has turned out that I really do have one. This may explain my ability to read massive amounts of detailed literature and sort out the details. In my case, abstract thought based on language has been replaced with high-speed handling of hundreds of 'graphics' files. Studies of patients with fronto-temporal dementia show that language-based thinking can cover up detailed visual thinking and music. As the disease destroys the frontal lobe and the language parts of the brain, art and music talent can emerge in people who had no previous interest in art or music (Miller et al. 1998, 2000; see also Snyder 2009).

Baron-Cohen, S. 2000. Is Asperger's syndrome and high functioning autism necessarily a disability? Dev. Psychopathol. 12, 489-500. (doi:10.1017/SO954579400003126)

Baron-Cohen, S., Ashwin, E., Ashwin, C., Tavassoli, T. & Chakrabarti, B. 2009. Talent in autism: hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1377-1383. (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0337)

Casanova, M. & Trippe, J. 2009. Radial cytoarchitecture and patterns of cortical connectivity in autism. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1433-1436. (doi: 10. 1098/rstb.2008.033 1)

Casanova, M. E. et al. 2006. Minicolumnar abnormalities in autism. Acta Neuropathol. 112, 287-303. (doi:10.1007/ s00401-006-0085-5)

Casanova, M. E., Switala, A. E., Tripp, J. & Fitzgerald, M. 2007. Comparative minicolumnar morphomery of three distinguished scientists. Autism 11, 557-569. (doi:10.1177/1362361307083261)

Courchesne, E., Redcay, E. & Kennedy, D. 2004. The autistic brain: birth through adulthood. Curr. Opin. Neurol 17, 489-496. (doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000137542.14610.b4)

Dawson, M., Soulieres, I., Gernsbacher, M. A. & Mottron, L. 2007. The level and nature of autistic intelligence. Psychol. Sci. 18, 657-662. (doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280. 2007.01954.x)

Fitzgerald, M. & O'Brien, B. 2007 Genius genes, how Asperger talents changed the world. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Co.

Freedman, D. J., Riesenhubert, M., Poggio, T. & Miller, E. X. 2001 Categorical representation of visual stimuli in the primate prefrontal cortex. Science 291, 312-315. (doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502-312)

Grandin, T 1995 Thinking in pictures. New York, NY: Vintage Press Random House. (Expanded version 2006)

Grandin, T 2000 My mind as a web browser--how people with autism think. Cerebrum 9, 13-22.

Grandin, T. 2002. Do animals and people with autism have true consciousness. Evol. Cogn. 8, 241-248.

Grandin, T. & Johnson, C. 2005. Animals in translation. New York, NY: Scribner.

Happe, F. & Frith, U. 2009. The beautiful otherness of the autistic mind. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1345-1350. (doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0009)

Happe, F. & Vital, P. 2009. What aspects of autism predispose to talent? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1369-1375. (doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0332)

Kana, R. K., Keller, T A., Cherkassky, V. L., Minshew, N. J. & Just, M. A. 2006. Sentence comprehension in autism: thinking in pictures with decreased functional connectivity. Brain 129(Pt 9), 2484-2493. doi: 10. 1093/brain/awl164)

Ledgin, N. 2002. Aspergers and self esteem. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons.

Miller, B. L., Cummings, J., Mishkin, F., Boone, B., Prince, F., Ponton, M. & Cotman, C. 1998. Emergence of artistic talent in fronto-temporal dementia. Neurology 51, 978-981.

Miller, B. L., Boone, K., Cummings, J. L., Read, S. L. & Mishkin, F. 2000. Functional correlates of musical and visual ability in fronto-temporal dementia. Br. J. Psychiatry 176, 458-463. (doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.5.458).

Minshew, N. J. & Williams, D. L. 2007. The new neurobiology of autism: cortex, connectivity, and neuronal organization. Arch. Neurol. 64, 945-950. (doi:10.1001/archneur.64.7.945)

Minshew, N. J., Meyer, J. & Goldstein, G. 2002. Abstract reasoning in autism--a disassociation between concept formation and concept identification. Neuropsychology 16, 327-334. (doi:10.1037/0894-4105.16.3.327)

Mummery, C. J., Patterson, K., Hodges, J. R. & Price, C. J. 1998. Functional neuroanatomy of the semantic system: divisible by what? J. Cogn. Neurosci. 10, 766-777. (doi: 10.1162/089892998563059)

Newport, J., Newport, M. & Dodd, J. 2007. Mozart and the whale. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Scheuffgen, K., Happe, F., Anderson, M. & Frith, U. 2000 High 'intelligence,' low 'IQ'? Speed of processing and measured IQ in children with autism. Dev. Psychopathol. 12, 83-90. (doi:10.1017/SO95457940000105X)

Snyder, A. 2009. Explaining and inducing savant skills: privileged access to lower level, less-processed information. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1399-1405. (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0290)

Tammet, D. 2006. Born on a blue day. New York, NY: Free Press.

Click here to return to the Homepage for more information on animal behavior, welfare, and care.

Click here to return to the Homepage for more information on animal behavior, welfare, and care.