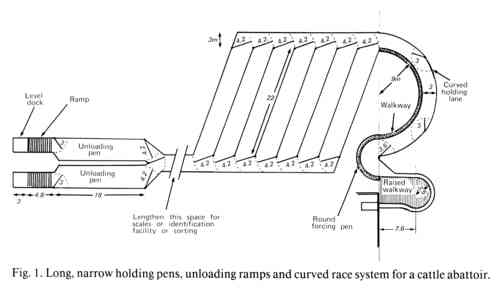

Fig. 1. Long, narrow holding pens, unloading ramps and curved race system for a cattle abattoir.

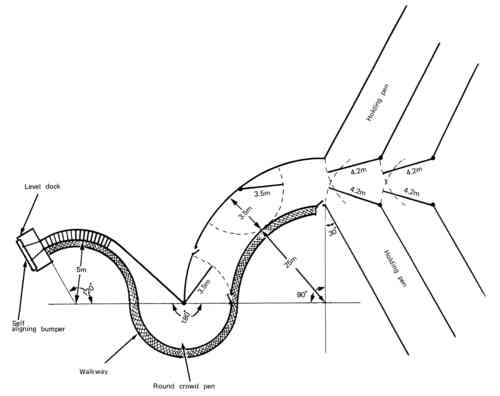

Holding pens and loading facilities are used in abattoirs, saleyards, stockyards, and sorting facilities. Long, narrow pens are recommended where animals enter through one end and leave through the other. Constructing the pens on a 60-80° angle eliminates sharp 90° corners. Flooring in holding pens should be non-slip. Indoor holding pens should have even, diffuse lighting that minimizes shadows. Cattle, pigs and sheep have a tendency to move more easily from a dimly illuminated area to a more brightly illuminated area. Facilities should be designed to minimize excessive noise.

In large facilities more than one unloading ramp may be required to facilitate prompt unloading. During warm weather prompt unloading is essential because heat rapidly builds up in a stationary vehicle. Ideally, holding pens should be built at truck height to eliminate ramps.

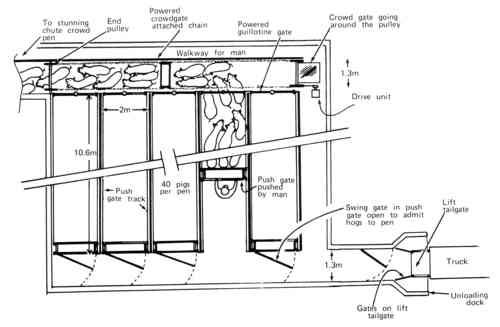

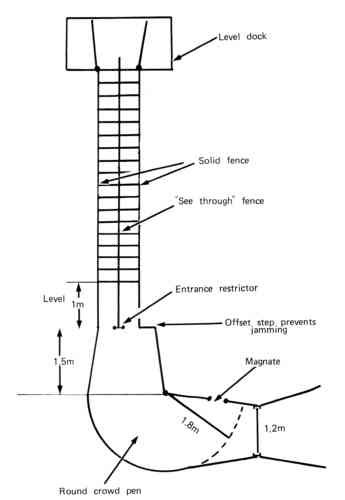

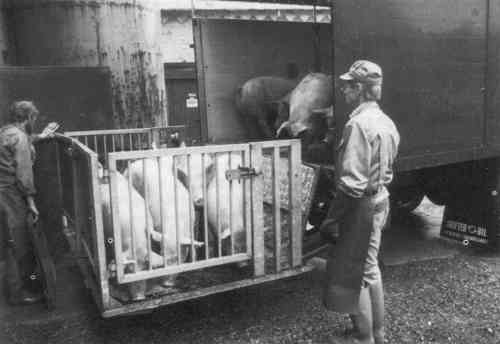

The maximum recommended angle for adjustable ramps for cattle, pigs, and sheep is 25° . Twenty degrees is the maximum recommended angle for non-adjustable ramps. For pigs, 15° is recommended. Ramps should have a level dock at the top equal to one animal body length. Stairsteps are recommended on concrete ramps. Recommended dimensions are a 30 cm minimum tread width and a 10 cm rise for cattle, and a 25 cm tread width and 5 cm rise for slaughter weight pigs. Both loading and unloading ramps should have solid fences. The crowd pen that leads to the ramp should also have solid sides and it must never be placed on a ramp. Crowd pens must be level. Single file, curved ramps with solid fences are very efficient for loading cattle onto trucks. Ramps used for unloading only should be 2.5 to 3-m wide to provide animals with a clear exit off the vehicle. In Denmark and other Scandinavian countries trucks used for transporting pigs are equipped with a hydraulic tailgate lift. Well designed holding pens and loading ramps can help reduce bruises and stress.

The basic principles of design are universal for all facilities but the purpose of the facility will affect certain parts of its design. For example, American and Australian trucks hold more animals than trucks in some European countries. This will affect the size of the holding pens. When a holding facility is designed, space must be allocated for specialized functions such as weighing, sorting, washing, or checking animal identification. To avoid serious design mistakes, the designer must fully understand the specific handling requirements of the country or region where the facility will be located.

Fig. 1. Long, narrow holding pens, unloading ramps and curved race system for a cattle abattoir.

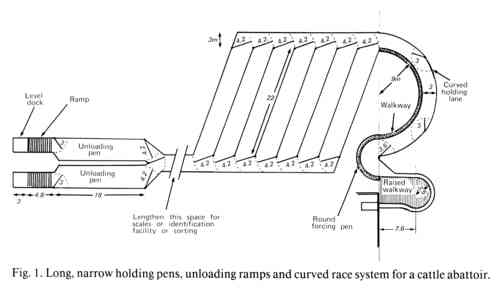

Fig. 2. Diagonal holding pens in a large pig abattoir.

Pigs present some practical problems. In the U.S.A., pigs are transported in trucks with a capacity of > 200 animals. However, they are fattened in much smaller groups. Observations at U.S. abattoirs; indicate that mixing 200 pigs from three or four farms resulted in less fighting than mixing 6-40 pigs. One advantage of the larger group is that an attacked pig has an opportunity to escape. Price and Tennessen (1981) found a tendency towards more DFD carcasses and hence more stress when small groups of 7 bulls were mixed, compared with larger groups of 21 bulls.

| Animals handled (h1) | Pen width (m) | Alley width (m) |

|---|---|---|

| < 4001 | 2 | 1.3 |

| > 4002 | 3-4.2 | 2.5-3 |

| Method of driving cattle | Pen width (m) | Alley width (m) |

|---|---|---|

| On foot | 3.5-4.2 | 3 |

| On horseback and on foot | N/A | 3.5 |

| On horseback | N/A | 4.2 |

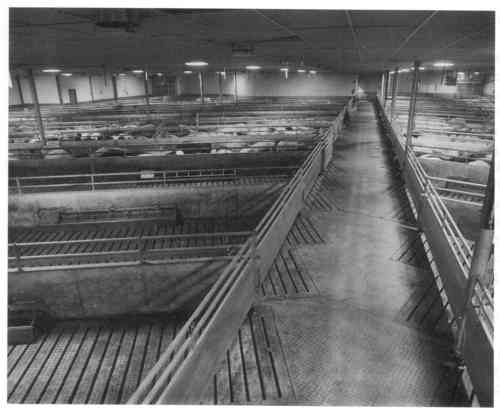

Fig. 3. Danish pig lairage with push gates and a power crowd gate.

In abattoirs, concrete slats may be used in livestock holding pens, but the drive alleys should have a solid concrete floor. Slats or gratings used in pig and sheep facilities should face in the proper direction. Sheep move more easily when they walk across the slats instead of parallel with them (Kilgour, 1971; Hutson, 1981 ). Figure 2 shows the correct orientation of slats in holding pens. The floor appears more solid when the animals walk across the slats. To facilitate animal movement, the animals must not be able to see light or reflections off water under the slats.

Animals will balk at sudden changes in floor texture or color. Flooring surfaces should be uniform in appearance and free from puddles (Lynch and Alexander, 1973). In facilities that are washed, concrete curbs may be installed between the pens to prevent water in one pen from flowing into another. Drains should be located outside the areas where animals walk. Livestock will balk at drains or metal plates across an alley (Grandin, 1987). Flooring should not move or jiggle when animals walk on it. Flooring that moves causes swine to balk (Kilgour, 1988).

All gates should be equipped with tie-backs to prevent them from swinging out into the alley. Guillotine gates should be counter-weighted and padded on the bottom (Grandin, 1983).

Livestock have sensitive hearing and they are stressed by excessive noise (Kilgour and de Langen, 1970; Kilgour, 1983). In steel facilities, gate strike posts should have rubber stops to reduce noise. Air exhausts on pneumatically powered gates should be piped outside (Grandin, 1983). If hydraulics are used to power gates, the motor and pump should be located away from the animals. Cattle held overnight in a noisy yard close to the unloading ramp were more active and had greater bruising compared with cattle held in a quiet pen (Eldridge, 1988).

In some facilities, unloading pens (Fig. I ) will be required. These pens enable animals to be unloaded promptly prior to sorting, weighing, or identification checking. After one or more procedures are performed the animals move to a holding pen.

Loading dock height varies depending on the types of vehicles used. If vehicle heights vary by a few centimeters, construction of nonadjustable ramps is recommended, even with the lowest vehicles used. This will enable the crossover bridge that is attached to the higher vehicles to be used more effectively.

Fig. 4. Crowd pen and ramp system for loading pigs onto trucks that have a narrow entrance door.

Fig. 5. The "see through" partition promotes following. The outer fences of this loading ramp are solid.

Recommended dimensions for stairsteps are a 30 cm minimum tread width and a 10 cm rise for cattle, and a 2 5 cm tread width and a 5 cm rise for slaughter weight pigs (U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 1967; Grandin, 1980c, 1982). The steps should be grooved to provide a non-slip surface. When cleats are used, they should be spaced 20 cm apart for large cattle and slaughter weight pigs (Mayes, 1978). The 20 cm is measured from the beginning of one cleat to the beginning of the next cleat. For small, 16 kg pigs, maximum cleat spacing is 10 cm apart (Phillips et al., 1987). Spacing the cleats 5 cm apart improved traction. During a choice test, small pigs readily walked up steep ramps with the narrower spacing (Phillips et al., 1990). Possibly, the 20 cm spacing recommended by Mayes ( 1978) for slaughter weight pigs should be decreased. On outdoor ramps that become covered with ice, closely spaced cleats may be more likely to become slick.

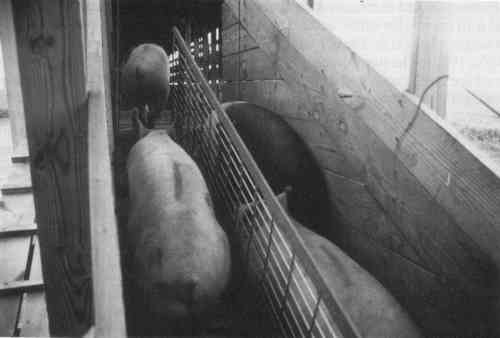

For all species, solid sides are recommended on both the ramp and the crowd pen which leads to the loading ramp (Rider et al., 1974; Brockway, 1977; Grandin, 1980a,b, 1982; Vowles et al., 1984). For operator safety, mangates must be constructed so that people can escape charging cattle. The crowd gate should also be solid to prevent animals from turning back. Wild animals tend to be calmer in facilities with solid sides. In holding pens, solid pen gates along the main drive alley facilitate animal movement (Fig. 2) (Grandin, 1980b).

When young pigs were given a choice of ramps, they preferred a ramp with either solid or woven wire sides (Phillips et al., 1987). Ramps with vertical or horizontal barred sides were avoided. The overhead lighting used in the indoor experiment may have made the wire mesh appear solid.

Fig. 6. Curved, cattle loading ramp with a round crowd pen. A double row of long, narrow holding pens is constructed on both sides of a central alley.

Cattle and sheep crowd pens should have one straight fence and the other fence should be on a 30° angle (Meat and Livestock Commission). This layout should not be used with pigs as they will jam at the ramp entrance. Jamming is very stressful for pigs (van Putten and Elshof, 1978). A single, offset step equal to the width of one pig should be used to prevent jamming at the entrance of a single-file ramp (Grandin, 1982, 1987). Jamming can be further prevented by installing an entrance restrictor at single-file race entrances. The entrance of the single-file race should provide only 0.5 cm on each side of each pig. The double-race ramp in Fig. 4 also has a single offset step to prevent jamming.

Fig. 7. A round crowd pen with solid fences leads up to a curved ramp for loading cattle.

Fig. 8. In Denmark, trucks are equipped with a tailgate lift for loading and unloading pigs.

Barton-Gade, P., 1985. Developments in the pre-slaughter handling of slaughter animals. Proceedings of the European Meeting of Meat Research Workers, Albena, Bulgaria. Institute of Meat Industry, Sofia, Paper 1: 1, pp. 1-6.

Barton-Gade, P., 1989. Pre-slaughter treatment and transportation research in Denmark. Proceedings, 35th International Congress of Meat Science and Technology, Copenhagen, August 20-25, 1989. Danish Meat Research Institute, Roskilde.

Brockway, B., 1977. Planning a sheep handling unit. Farm Buildings Centre. National Agriculture Centre, Kenilworth, pp. 1-30.

Canadian Meat Council, 1980. Guide to PSE Pork. Canadian Meat Council, Islington, Ont., pp. 1-9.

Eldridge, G.A., 1988. The influence of abattoir lairage conditions on the behaviour and bruising of cattle. Proceedings of the 34th International Congress of Meat Science and Technology, Brisbane Qld., 29 August2 September 1988. Livestock and Meat Authority of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld.

Fraser, D., Phillips, P.A. and Thompson, B.K., 1986. A test of a free-access two level pen for fattening pigs. Anim. Prod., 42: 269-274.

Grandin, T., 1979. Designing meat packing plant handling facilities for cattle and hogs. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng., 22: 912-917.

Grandin, T., 1980a. Observations of cattle behavior applied to design of cattle handling facilities. Appl. Anim. Ethol., 6: 19-3 1.

Grandin, T., 1980b. Livestock behavior as related to hand4ng facility design. Int. J. Stud. Anim. Probl., 1: 33-52.

Grandin, T., 1980c. Bruises and carcass damage. Int. J. Stud. Anim. Probl., 1 121-137.

Grandin, T., 1980d. Designs and specifications for livestock handling equipment in slaughter plants. Int. J. Stud. Anim. Probl., 1: 178-200.

Grandin, T., 1982. Pig behaviour studies applied to slaughter plant design. Appl. Anim. Ethol., 9: 141151.

Grandin, T., 1983. Welfare requirements of handling facilities. In: S.H. Baxter, M.R. Baxter and J.A.D. MacCormack (Editors), Farm Animal Housing and Welfare. Martinus Nijhoff, Dordrecht, pp. 137-149.

Grandin, T., 1987. Animal handling. In: E.O. Price (Editor), Farm Animal Behaviour. Vet. Clin. N. Am. 3: 323-338.

Hitchcock, D.K. and Hutson, G.D., 1979. The movement of sheep on inclines. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. Husb., 19: 176-182.

Hutson, G.D., 1981. Sheep movement on slotted floors. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. Husb., 21: 474479.

Kenny, F.J. and Tarrant, P.V., 1987. The behaviour of young Friesian bulls during social regrouping at an abattoir. Influence of an overhead electrified wire grid. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 18: 233-246.

Kilgour, R., 1971. Animal handling in works; pertinent behaviour studies. In: Proceedings of the 13th Meat Industry Research Conference, Hamilton, New Zealand, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, pp. 9-12.

Kilgour, R., 1976. The behaviour of farmed beef bulls. N.Z. J. Agric., 13 (6): 31-33.

Kilgour, R., 1978. The application of animal behaviour and the humane care of farm animals. J. Anim. Sci., 46: 1478-1486.

Kilgour, R., 1983. Using operant test results for decisions on cattle welfare. Proceedings of a Conference on the Human-Animal Bond, Minneapolis, MN. College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Kilgour, R., 1988. Behaviour in the pre-slaughter and slaughter environments., Proceedings of the International Congress of Meat Science and Technology, Part A, Brisbane, Qld., 29 August-2 September, 1988. Livestock and Meat Authority of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld., pp. 130-138.

Kilgour, R. and de Langen, H., 1970. Stress in sheep from management practices. Proc. N.Z. Soc. Anim. Prod., 30: 6 5-76.

Livestock Conservation Institute, 1988a. Livestock Trucking Guide. Livestock Conservation Institute, Madison, WI, pp. 1- 15.

Livestock Conservation Institute, 1988b. Livestock Handling Guide. Livestock Conservation Institute, Madison, WI, pp. 1- 15.

Lynch, J.J. and Alexander, G., 1973. The Pastoral Industries of Australia. University Press, Sydney,pp.371-400.

Marshall, B.L., 1977. Bruising in cattle presented for slaughter. N.Z. Vet. J., 25: 83-86.

Mayes, H.F., 1978. Design criteria for livestock loading chutes. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng., St. Joseph, MI, Tech. Pap. No. 78-6014, pp. 1-9.

Mayes, H.F. and Jesse, G.W., 1980. Heartrate data of feeder pigs. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. St. Joseph, MI, Tech. Pap. No. 80-4023, pp. 1-8.

Meat and Livestock Commission. Cattle handling. Livestock Buildings Consultancy, Meat and Livestock Commission, Milton Keynes, pp. 1-7.

Midwest Plan Service, 1980. Structures and Environment Handbook. Iowa State University, Ames, IA, I Oth edn., p. 319. DESIGN OF LOADING FACILITIES AND HOLDING PENS 201

Phillips, P.A., Thompson, B.K. and Fraser, D., 1987. Ramp designs for young pigs. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng., St. Joseph, MI, Tech. Pap. No. 87-4511.

Phillips, P.A., Thompson, B.K. and Fraser, D., 1988. Preference tests of ramp designs for young pigs. Can. J. Anim. Sci., 68: 41-48.

Phillips, P.A., Thompson, B.K. and Fraser, D., 1989. The, importance of cleat spacing in ramp design for young pigs. Can. J. Anim. Sci., 69: 483-486.

Puolanne, E. and Aalto, H., 198 1. The incidence of dark cutting beef in young bulls in Finland. In: D.E. Hood and P.V. Tarrant (Editors), The Problem of Dark Cutting Beef. Martinus Nijhoff, London, pp. 462-475.

Price, M.A. and Tennessen, T., 198 1. Preslaughter management and dark cutting carcasses in young bulls. Can. J. Anim. Sci., 61: 205-208.

Rider, A., Butchbaker, A.F. and Harp, S., 1974. Beef working, sorting and loading facilities. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng., St. Joseph, MI, Tech. Pap. No. 74-4523.

Stevens, R.A. and Lyons, D.J., 1977. Livestock bruising project: Stockyard and crate design. National Materials Handling Bureau, Department of Productivity, Australia, pp. 1-20.

Stricklin, W.R., Graves, H.B. and Wilson, L.L., 1979. Some theoretical and observed relationships of fixed and portable spacing behavior in animals. Appl. Anim. Ethol., 5: 201-214.

Tennessen, T. and Price, M.A., 1980. Mixing unacquainted bulls: The primary cause of dark cutting beef. 59th Annu. Feeder's Day Rep., Agric. For. Bull., University of Alberta, Alta., pp. 34-35.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1967. Improving services and facilities at public stockyards. Agriculture Handbook 337, Packers and Stockyards Administration USDA, Washington, DC, pp. 147.

Van Putten, G., 198 1. Handling slaughter pigs prior to loading and unloading on a lorry. Paper presented at the Seminar on Transport, C.E.C., Brussels, July 7-8, 198 1.

Van Putten, G. and Elshof, W.J., 1978. Observations on the effect of transport on the well being and lean quality of slaughter pigs. Anim. Regul. Stud., 1: 247-27 1.

Vowles, W.J., 1985. The design of saleyards. Workshop on cattle handling procedures and facilities, Rutherglen, 18-22 February 1985.

Vowles, W.J., Eldridge, G.A. and Hollier, T.J., 1984. The behaviour and movement of cattle through forcing yards. Proc., Aust. Soc. Anim. Prod., 15: 766.

Weyman, G., 1987. Unloading and loading facilities at livestock markets. Council of National and Academic Awards, Environmental Studies, Hatfield Polytechnic, Hatfield.

Click here to return to the Homepage for more information on animal behavior, welfare, and care.

Click here to return to the Homepage for more information on animal behavior, welfare, and care.